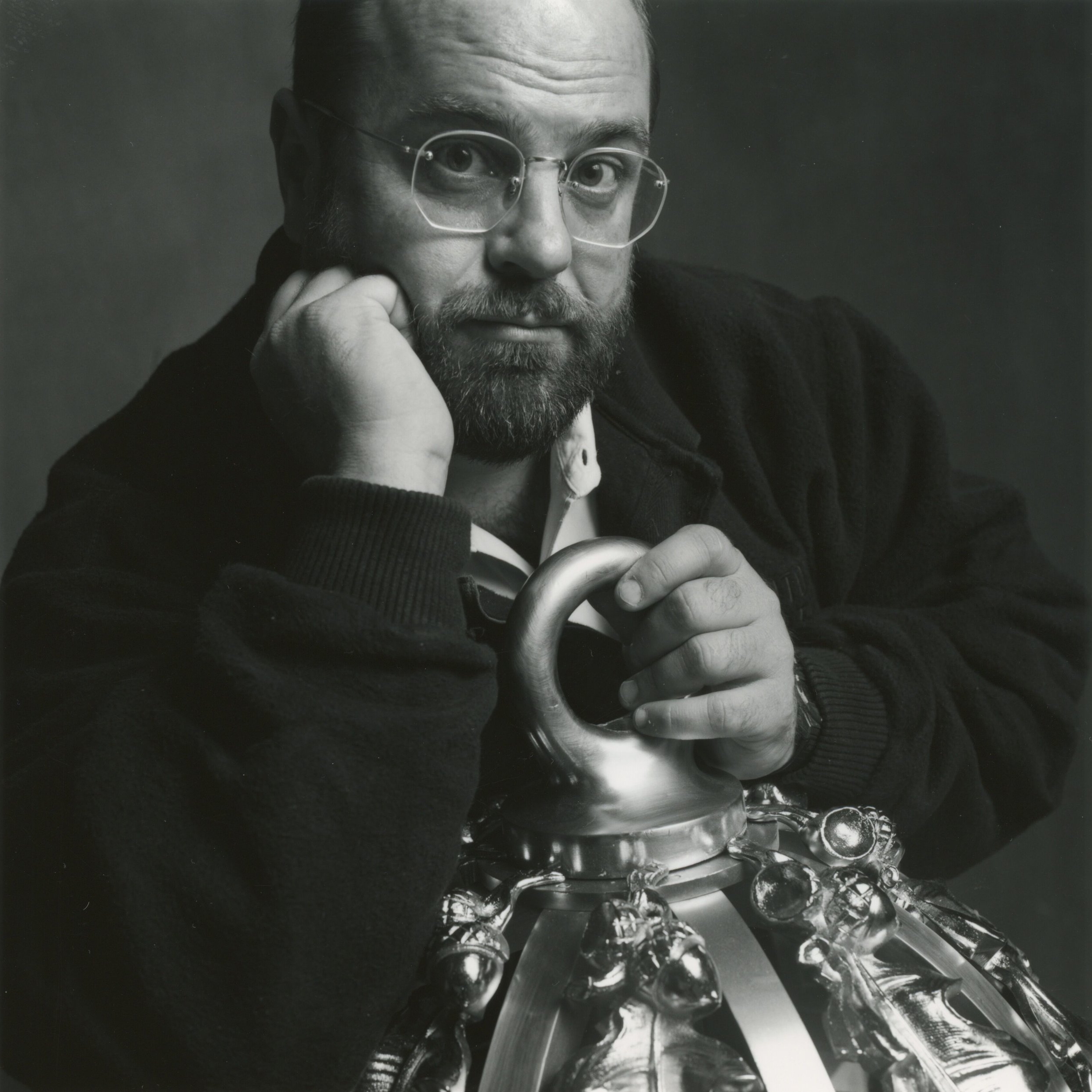

One of the things that can be difficult about our work here at Historical Arts & Casting is communicating the complexity of manufacturing something when its appearance is deceptively simple. For example, toward the end of 2018, on our Instagram feed, we published a couple photographs of a cast bronze door frame for a door that we were making at that time. Looking back on the images, although they clearly show a beautiful cast, thick-walled bronze frame, they really only tell part of the story.

Some of the factors that contribute to its complexity are its scale, its low production quantity, features added during the fabrication stage, and the finish on this frame.

At first glance, the published images do not do a very good job at revealing this piece’s scale. In reality, that door frame is over 12” wide and about 10’ tall. As shown in the images, each jamb is made up of two castings, each weighing approximately 8-9 pounds per linear foot. The physical scale of these bronze parts adds to their complexity in many ways. For one, our pattern makers make the patterns in such a way to compensate for the shrinkage factor relative to the material being poured. During the mold-making process in the foundry, the parts must be gated in a way to try to counteract the anticipated warping of the final part as it cools. Additionally, the sand molds for such large parts must be reinforced in ways molds for smaller parts need not. The foundry men must also manage the temperature of the bronze well, so as not to cause flaws such as heat-tearing and cold-pours. In addition, handling and moving these elements around the shop is made more difficult by their size and weight.

Scale is not only a function of an element’s size, but is is also related to its production quantity. In this case we were making only one of these frames—so the complexity comes in the effort to get its manufacture right, in every way, the first time. To be sure, making a product with a high production volume also has its own set of challenges—but when only one of something is being sold to a customer, the manufacturer really only wants to make it once, as there is very little room for error. Having to remake something because of an unforeseen issue or a mistake can eat up planned profits quickly when producing in low quantities. Consequently, there are fewer and fewer companies out there that are willing to take that risk. For decades, low production quantities have been a cornerstone of Historical Arts’ business, and as such, we have become accustomed to taking on this challenge.

The addition of machined and fabricated features to these castings is another layer of complexity relative to this door frame—and doing so only builds on the risk level for its low production quantity mentioned previously. The additional features in this frame include machined recesses for the hinges, pivots, the power assist motor access in the head, and the mitered corners where the jambs meet the head, as well as channels for the inclusion of weather-stripping. A mistake in adding any of these features could result in the need to make additional castings—which would again erase some of the profit potential for this product.

The last complexity factor we will cover on this project is the final finish of the door frame as seen, in-process, throughout the images in the article. This frame is finished with a directionally grained, non-oxidized treatment, which is sealed with a clear wax. Any flaw in the casting is easily discernible with this type of finish. Great care must be taken to apply this treatment, which is all done at the hands of our most skilled finishers—some of whom have more than 25 years of experience.

In the end, once the door and this frame are installed in their final location, the vast majority of people who pass through this door opening will do so with little awareness of what went into its manufacture. That really is a good thing—for elements like this should not necessarily draw attention to themselves, but rather contribute to the whole. Their value lies in being a part of the logical, balanced beauty of the overall architectural experience of which they are a part. Because of the materials used, the features added, and the skills and methods employed, their long-lasting, low maintenance lifespan will be appreciated by those who know.